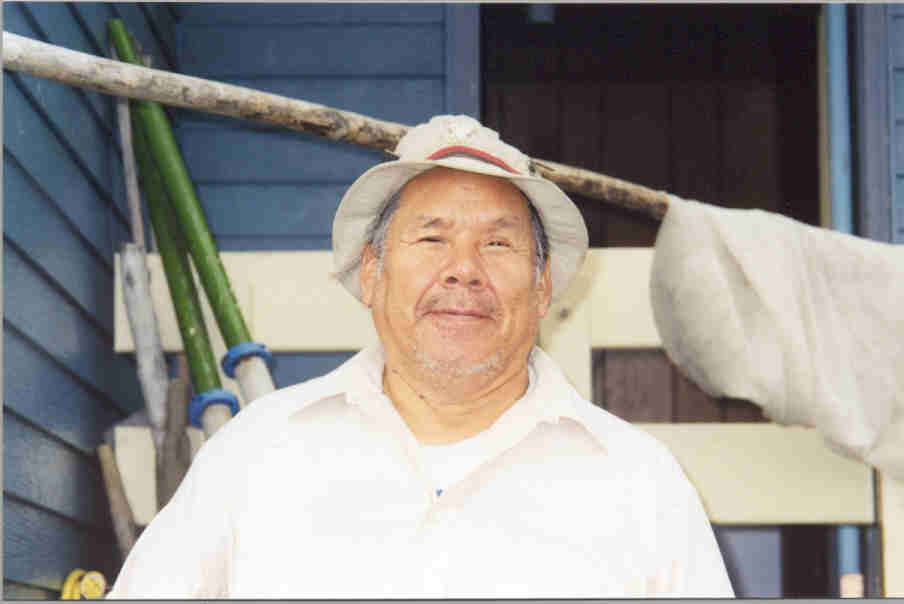

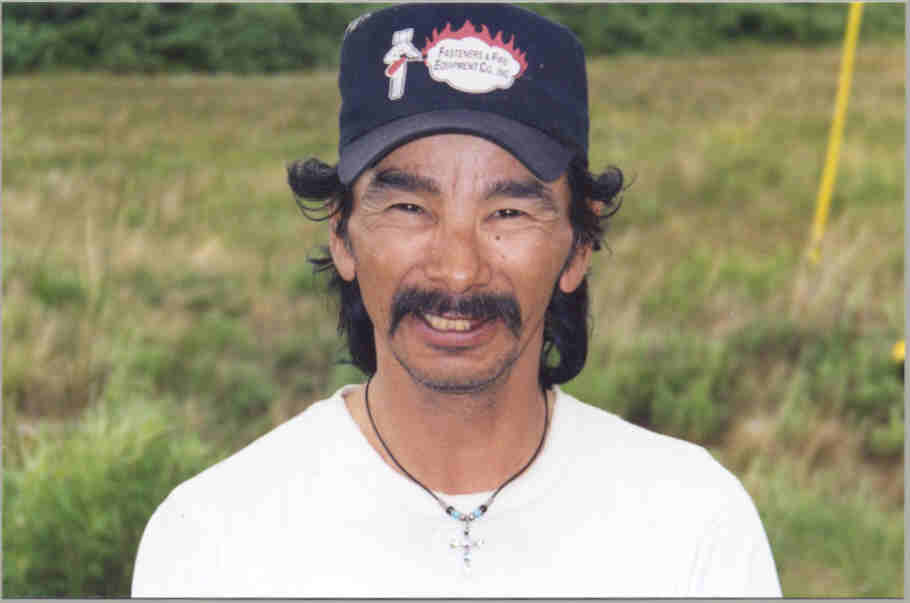

It's Thursday morning in the small town of Teller, Alaska, about fifty miles from Nome.  As a weather bulletin warning of high winds blares from a nearby radio, Thomas Ablowalak and his uncle Norbert Kakaruk, members of the Kauwerak tribe, are making plans to boat 50 miles inland.

As a weather bulletin warning of high winds blares from a nearby radio, Thomas Ablowalak and his uncle Norbert Kakaruk, members of the Kauwerak tribe, are making plans to boat 50 miles inland.

Thomas and Norbert pay a lot of attention to the weather. They have to. They hunt and fish in the wild's of Alaska and today they're going to the village where they were born and raised: Mary's Igloo. It was in that village where their ancestors passed down the story of the year with two winters.

Norbert says some legends are just stories. But this one really happened.

Thomas and Norbert pay a lot of attention to the weather. They have to. They hunt and fish in the wild's of Alaska and today they're going to the village where they were born and raised: Mary's Igloo. It was in that village where their ancestors passed down the story of the year with two winters.

Norbert says some legends are just stories. But this one really happened.

Our mother was telling us everything about it. She said that it was real hard for everybody. One summer nobody had salmon hanging. She told us and it was true. But some people got Tom Cods and something -- after July was over. Somehow the weather got warm enough. But it was too late for berries and greens. They thought it was going to be summer right away. But the ice came in from the ocean and it never really get warm. Everything was really bad that year. No Salmon, no greens because it was too cold.

By noon the weather report is more promising, and it seems the storm will abate. But as Thomas and Norbert get ready to visit their old village they keep their ears  tuned for news of any unexpected weather changes.

tuned for news of any unexpected weather changes.

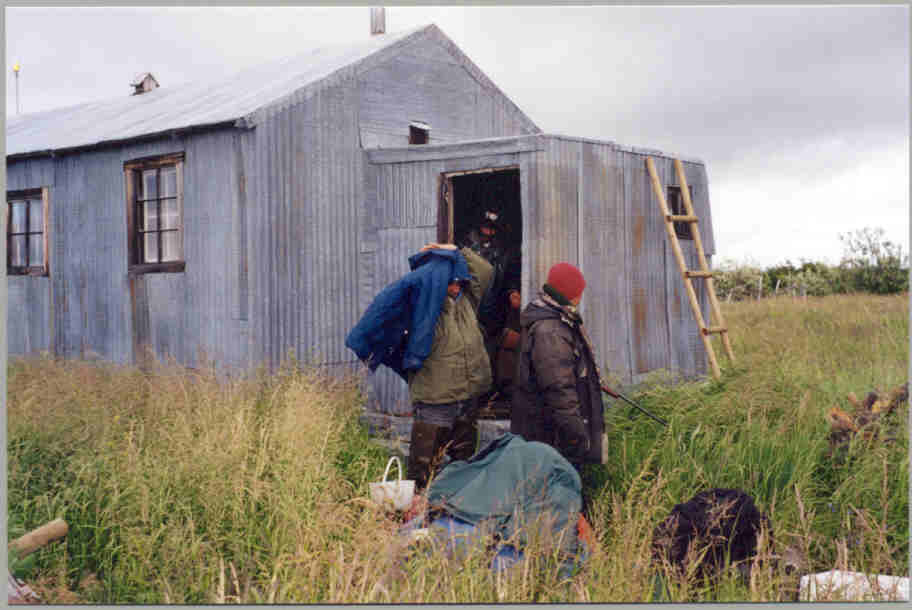

Twenty miles outside Teller,  the travelers take a break from the frigid wind and pounding waves on the river. They take refuge in a cabin,a rustic tar-paper shack, along the shore. On a recent visit here, Norbert and his sister beat a hasty retreat after a close call with a grizzly. Soon, they're on their way again in the Arctic twilight. At this time of year the sun sets for only a few hours. Time seems suspended.

the travelers take a break from the frigid wind and pounding waves on the river. They take refuge in a cabin,a rustic tar-paper shack, along the shore. On a recent visit here, Norbert and his sister beat a hasty retreat after a close call with a grizzly. Soon, they're on their way again in the Arctic twilight. At this time of year the sun sets for only a few hours. Time seems suspended.

The small motorboat moves through a narrow canyon with steep walls. Just ahead, the walls melt away and straits become an inland sea. Winds whip across its great length raising terrific waves.

Battered by white caps on the open waters, they follow the rules of survival passed down through the generations. Surviving in this kind of climate means you have to think ahead - know how to read the signs of nature, the cycle of the year. Norbert explains:

April and May and June. That's the spring time when you have the food for the summer and early fall. Late August, September and October, you put your supplies for the rest of the year. Then late October, November and December you don't have to really rush and put them away. You always have to make sure they are covered or put away where they are safe. December January and March, snow is so deep. A lot of time you dig a hole if you have some gunny sacks-you make a hole--and bury them with snow.

The town of Mary's Igloo,  where the two Eskimos are going was a gold-rush boomtown and was once the tribe's largest settlement. Now it's abandoned. But even today, for those who still follow traditional ways, it is, Norbert says, a source for winter staples.

where the two Eskimos are going was a gold-rush boomtown and was once the tribe's largest settlement. Now it's abandoned. But even today, for those who still follow traditional ways, it is, Norbert says, a source for winter staples.

That's why everyone is going to Mary's Igloo for certain kind of food. The certain kind of food they need for the spring break up.

When we arrive at our destination Thomas and Norbert beach the boat beneath a steep bank, and immediately spot trouble: fresh bear tracks.

Want me to jump out? No we're okay -What the hey. Bear tracks! Get the guns out. Bear tracks! Bear tracks Right there.Fresh ones. Get the guns out. I've got mine handy. Fresh ones . Very Fresh.

A grizzly is on the prowl. Thomas says the menacing tracks were left by a big one, perhaps a man-killer. Guns in hand, Thomas and Norbert make noises to roust the bear and send it on its way.

The bear could be hiding in the tall grass above the bank. An accidental encounter could be deadly.

When Thomas and Norbert were young, bears didn't harass people here. Now across much of the mostly emptied region bears have practically taken over. Norbert fires his rifle in the air to ward off the bear. Legend has it that before the year of no summer the Kauwerak people were also at odds with the animal kingdom and the calamitous weather was divine punishment.

Norbert fires his rifle in the air to ward off the bear. Legend has it that before the year of no summer the Kauwerak people were also at odds with the animal kingdom and the calamitous weather was divine punishment.

After a sleepless night Thomas and Norbert survey their clan's tin and tar paper homes. One shack's nasty jagged gash tells the story of a hungry bear in search of food. Other houses are deeply scored by bear claws.

Jesus Christ. Look at that! They ripped the tin, ripped the lumber. Look. Look here.

Thomas and Norbert are getting more and more nervous. In the wee hours they spied a man-size bear, but it disappeared into the a thicket. One or more grizzlies may be hiding in the waist-high grass. Even armed with two high-powered rifles, the men are jumpy and anxious to be on their way.

There could be more bears waiting down wind. The two travelers have done what they came to Mary's Igloo for, to check up on their family's property. It would be senseless to stay any longer with fearless grizzlies lurking.

The weather has broken as they begin the long journey home. The damp riverbanks provide fresh evidence of the dangers in Mary's Igloo.

There are some more bear tracks on the opposite side of the river. They're around. They're here. Look at us now. We can't go … without a rifle or a high-powered weapon.

There are some more bear tracks on the opposite side of the river. They're around. They're here. Look at us now. We can't go … without a rifle or a high-powered weapon.

Surviving out here miles from a road or electric line means knowing how to read tracks and other signs of nature such as the appearance of the moon. Norbert shared one last piece of wisdom from his elders.

I remember our grandfather told us if it stands up straight up and down for a day. .. that shows we're going to have sunny days for a month or so. But if it leans to the south. Like if it's a half a moon or a quarter moon and it leans to the south on the top side, that shows there's lots of north wind-strong north wind. And if its face up -- the top of the moon tips to facing the north and the bottom faces south-that's a south wind. Wet weather coming.